It’s late and I can’t sleep so I thought I’d try writing a post for the morning. I don’t really know if I have a point to make here, it’s an experiment and I’m just sort of rambling, but you have to forgive me because it’s not very often I can find relevance I can make a tenuous connection between my fascination with the chansons de geste / chivalric romance and whatever’s going on in the world today, so I have to leap at whatever presents itself.

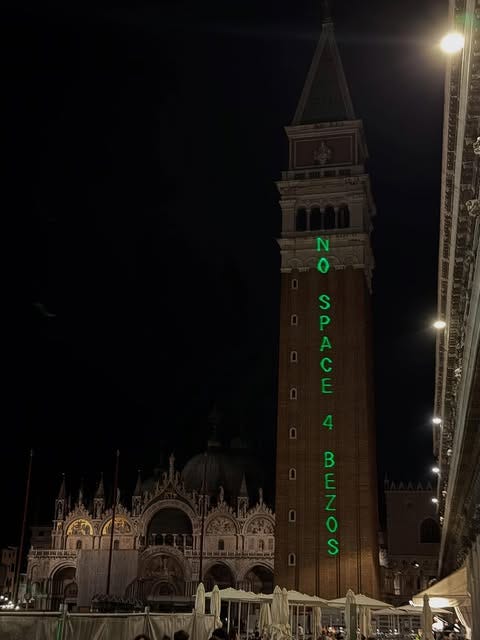

So, you’ve probably heard that Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, is getting married to a former Fox News host. You’ve probably heard about this because Bezos is throwing a $50 million wedding that’s basically shutting down Venice, treating the city as if it were an event venue. The details leaking out are obscene. The one I keep circling back to is that 90 private jets are flying in something like 200 guests. And here I always thought the point of a wedding was to spend time with other people. Venetians aren’t taking this lying down: the No Space for Bezos movement has formed to protest the event, and to call attention to the gross inequalities our capitalist system produces, and to how the rich are the prime contributors to runaway greenhouse gas emissions. Good on the Venetians, I say. The city belongs to its people, and Bezos deserves far worse than to have his wedding interrupted.

It reminds me of another (unwelcome?) guest to the city, in the 1480s. From 1482-4, Venice and Ferrara had been fighting the Salt War, so called because the major issue at stake was Ferrara’s right to run the salt pans at Comacchio, which would interfere with the Venetian monopoly, as they had their own salt works at Cervia. This time, the Venetians won. The war ended with a treaty signed in the town of Bagnolo,1 but to show there were no hard feelings between the elite, the Venetians invited Duke Ercole d’Este, the ruler of Ferrara, to Venice.

Before I started writing this post, I was convinced Ercole was heckled and booed by the people—I’m still sure that’s true, but I can’t find a citation for it and I’ve been looking through my notes for well over an hour now. He was definitely treated extremely well by the city’s elite: he was shown through the town, met with the Doge and senators, given a ride on the bucentaur (the state barge, akin to a Bezosian super yacht, though it should by noted though that bucentaurs were not unique to Venice, Ercole and his son both maintained their own state pleasure barges, as did Francesco Gonzaga), he toured the glassblowing workshops of Murano, and went with the Doge to watch a number of jousts (the sons of Robert da San Severino did quite well, if you were wondering). Ercole’s retinue numbered at least two hundred, and among these were the poet Count Matteo Maria Boiardo and the ducal official Niccolò Ariosto. Boiardo would go on to publish his Orlando Innamorato a year later, and Niccolò’s son would grow up to write its continuation, Orlando Furioso.

Things didn’t stay cordial between Venice and Ferrara for long. Tensions started to rise again after the Battle of Fornovo2, when most of Italy united to kick out the French. Ferrara fought on the anti-French side, but only halfheartedly, as the French had long been (and would continue to be) their best ally. When the news of the battle reached Venice, the boys of the town started singing an improvised song to mock Ferrara, even though they’d ostensibly been on the same side:

Marchexe di Ferrara, di la caxa di Maganza,

Tu perderà ’l stado, al dispetto dil Re di Franza

Marquis of Ferrara, of the House of Maganza,

thou shalt lose thy State, in spite of the King of France.

Supposedly “the artisans and shopkeepers offered to pay double taxes, if the Republic would assail Ferrara.”3 Ercole wasn’t in Venice at the time, presumably he was travelling home to Ferrara from the battlefield, but he would’ve heard all about it from his ambassador, and he would’ve heard taunts like that before. Probably on trips to Venice, but maybe elsewhere, too.

What interests me about that song is that first line, about the House of Maganza—that’s the house of Ganelon and an assortment of other villains from the chansons de geste, and by the 1490s there were centuries’ worth of nasty rumours going around that the House of Este was descended from the House of Maganza. The modern equivalent would be people genuinely believing a president or prime minister was descended from The Joker.4

Boiardo is usually given credit for changing that perception, as his poem switches the story. In the Innamorato, there’s a prophecy that the Saracen knight Ruggiero will fall in love with the lady knight Bradamante, convert, and found the House of Este. Better still, Ruggiero is given a genealogy that goes back to Hector of Troy, so there’s no way some other poet can tie Ganelon into the new family tree. It’s possible though that this convention was actually created by Boiardo’s contemporary, the poet Tito Vespasiano Strozzi, whose less well-known Borsiad also features a Trojan lineage for the Estensi, and even mentions Ruggiero and Bradamante.5 Tito was working on his poem from maybe the 1460s up until his death in 1505(6?), while Boiardo was writing his in the 1470s, published the first version in 1483, with the final version coming out a year after his death, in 1495. The two would have been friends, and it seems possible to me that they were collaborating to some small degree on this encomiastic lineage, of giving the Estensi honourable ancestors instead of scoundrels.

This is the part of the story where I’m supposed to tell you that the difference between now and then is that nowadays our oligarchs and despots should, if they won’t pay their fair share in taxes, at least be patronizing the arts like they did during the Renaissance. And that’s partly true, they should definitely be patronizing the arts: Mackenzie Scott, if you are reading this, please message me.

But here’s the thing, while Duke Ercole is often referred to as a patron of Boiardo and Strozzi (and his sons Duke Alfonso and Cardinal Ippolito are referred to as patrons of the poet Ludovico Ariosto, who continued to write about Ruggiero and Bradamante and their knightly adventures), the term patron here is an oversimplification. Duke Ercole kept Boiardo in high office and he banked with Strozzi, but he didn’t pay them for their poetry and there’s no indication that he was even all that fond of it (his daughter Isabella d’Este loved the Innamorato, but she was a notorious cheapskate). Strozzi and Boiardo were what Gundersheimer, in his book Ferrara: The Style of a Renaissance Despotism, classifies as Type I humanists: people who had an important role to play in society and who were artists in their abundant spare time. Even worse, no Type II humanists, “publish or perish humanists” as Gundersheimer calls them, produced any lasting literature in this time period, at least not in Ferrara..

My favourite poet from this time—my favourite poet of all time—is Ludovico Ariosto, a guy who desperately wanted to be a Type 1. He had talent and he would be famous within his own lifetime, but to get by he would always need to find some office to hold in the Este’s court, and they were always coming up with ways to cut off his salary. Lately, I’ve been trying to write a novel about a particularly eventful period of Ariosto’s life.6 And he had an eventful life. I’ll tell you about it some time. Among other things, he circulated satires. In private. They were mostly self-deprecating (self-deprecation doesn’t get you in trouble with the despot) but he was also a master of irony, and you can’t read his poetry and not see parts of it as a criticism of the Este—especially the parts that, on the surface level, read as praise. Although with that said, he also chickened out more than once, praising the worst Estensi crimes.

I don’t know what I’m trying to get at here. Ariosto doesn’t seem to have held a grudge against the Venetians, even though his family lost it’s property in the Salt War when he was young (his father surrendered Rovigo), and then Ferrara fought another war against Venice when he was of age. He had plenty of Venetian friends, Pietro Bembo chief among them.7 I guess I like to think Ariosto would be proud of his neighbours for opposing Bezos?

I don’t know what I’m trying to get at here. I’ve lost my train of thought. Oh, but I have two book recommendations that might be of interest, stuff I happened to be reading lately. The first is Venice's Secret Service: Organising Intelligence in the Renaissance by Ioanna Iodanou. It’s really interesting, especially the stuff about cyphers and the Council of Ten and the networks with Venice’s overseas colonies. The author is a business historian, though, and she keeps trying to make connections to human resource management theory or something, which I found a bit odd. The other book is The Revolt of Snowballs: Murano Confronts Venice, 1511 by Claire Judde De Lariviere. It’s a microhistory about a snowball fight that broke out during the ceremony to replace the podesta of Murano. It sounds like fun, but there was a whole investigation and trial afterwards, which is how we know about it. The stuff about the glassblowers is particularly fascinating. They kept their furnaces running for all but a few weeks in the summer. Wild. Actually, now that I think about it, the snowball fight probably is probably a better parallel to the Bezos protest than taunting Ercole. The people had a grudge against the outgoing podesta. If you’ve read about podestas, you’ll understand why people held grudges against them. Probably should’ve wrote about that. Oh well. Check out the books.

More:

Bembo's bad boarder

Heist Watch: Mythical Sword Edition

Bembo's Other Bad Boarder

The Necromancer of the Colosseum

Introducing Luigi Pulci

One Weird Naming Convention of Milan's Medium Elite Families

I appreciate the historian Chris Wickham, and I really need to read more of his stuff. His book Sleepwalking Into a New World looks at the emergence of communes in Italy in the middle ag…

Instagram | Goodreads | Letterboxd | Bluesky

The pot Ludovico Ariosto has cousin with a large estate in Bagnolo which Ludovico was due to inherit, but the Este family (who’d first given it to the cousin) decided to take it back for themselves. Ariosto sued the Este despite being in their employ at the time. He was not successful.

Highly recommend War Nerd Radio episode 334 on Fornovo, with guest host Annibale.

This and the song from Dukes and Poets in Ferrara by Edmund Gardner.

Or I guess Fidel Castro, if for some reason you see him as a bad guy to be descended from. Except no, because Castro really existed.

For more on Tito’s Borsiad, check out The neo-Latin historical epics of the north Italian courts: an examination of ‘courtly culture’ in the fifteenth century by Kristen Lippincott.

Mackenzie Scott, I am sooo serious, if you see this call me

Pietro Bembo moved to Venice when his father was appointed Visdomino, basically an official imposed by Venice on Ferrara to uphold salt and commerce regulations, Pietro went onto have an infamous affair with Lucrezia Borgia, first lady of Ferrara.