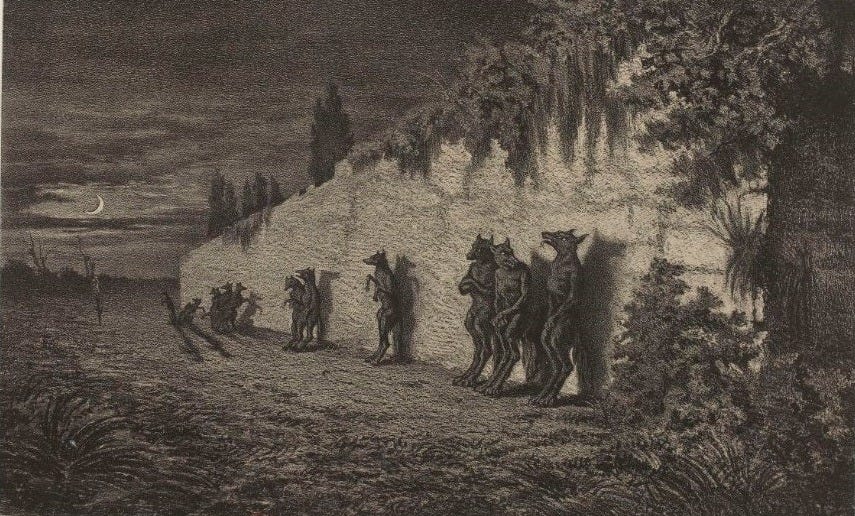

Pepys Show: werewolf edition

Awwwooooou (wolf howl) Adam's Notes for January 22, 2024

But keep the wolf far thence, that's foe to men,

For with his nails he'll dig them up again.

— John Webster, The White Devil (1612)

Pepys Show

March 1, 1660: walked about all day, hoping perchance to meet upon my cozen Richard, that we might go over the business of the last full moon and the fits of wolfing that did overtake us, which worries me greatly, I having been sore vexed of late by dreams of the foulest mongrel knavery and so do fear me the worst.

Did find him at his tailor’s with his sister Anne, and we three of us off to the Globe to broach a vessel of ale and discuss matters of the wolfing disease. Richard did say that he remembered it a miserable occasion, the worst fit in his seven years of it, and that he recalled digging up a great hole on Hampstead heath with my assistance, and therein burying the bones of some poor rascal we must have troubled upon. I did tell him about my vexing dreams and together we surmised it must have been the butcher, Vincent, who had been hounding Richard over a bill of 18L. Neither of us seeing him since, we did soon fear the worst and did not dare go to check upon his shop lest we be recognized, and so sent Anne in our stead to see if he is alive or no, she being less likely to attract suspicion and altogether less troublesome in her fits. We tarried late waiting for Anne’s report, quenching our thirst with a pot of ale and tasting sweet meats. Then I home to bed still much troubled by a fit which is now almost a fortnight past.

Wait a minute—that’s not Samuel Pepys!

It’s the beginning of my short story, Diary of the Wolf, out now in Old Moon Quarterly, Volume 6 (print version available soon).

I started writing it in March of last year. At the time I was in a bit of a slump, promising myself I’d try my hand at another short story but unable to come up with anything. I’m in a group chat on twitter with a focus on history and at the time we were doing a lot of laughing at the antics of the Samuel Pepys bot (sadly discontinued after 14 years due to Musk’s tinkering with Twitter API), and so I started tinkering around with the idea of a story set in Pepys’ world, written by a parallel diarist. I wrote the story over the course of the month, using each day of Pepys’ diary for March 1660 as inspiration for a day in my story’s diary.

It was a fun challenge. I wanted to capture something of Pepys’ language and antics while also including a strong speculative element. I went with lycanthropy for the speculative part, because werewolves rock and there’s natural connections with witch trials, which would’ve been part of living memory, and to a lesser extent with animal baiting, a cruel sport which was starting to make a comeback after being banned by Cromwell. I even managed to make a connection in the story to my beloved chansons de geste and to my favourite sword and sorcery story, Worms of the Earth.

Researching Pepys’ era was fun, the Samuel Pepys website is a wonderful resource, but all the same, trying my hand at historical fiction (well, historical fantasy) was a bit unnerving. It’s probably the least forgiving genre in terms of people giving you a hard time, everyone’s so keen to pick out anachronisms. I’m sure I’ve made a few mistakes (there’s a bit about the calendar year at the beginning that drove me crazy for the longest time and then last night I thought I’d got it completely wrong and had to go back to my notes to reassure myself). But all the same, it was a lot of fun to write. It felt more like piecing a puzzle together than writing normally does.

Pepys Show — for real this time

Pepys starts 1661 with a helpful summary on the state of his life and the kingdom:

At the end of the last and the beginning of this year, I do live in one of the houses belonging to the Navy Office, as one of the principal officers, and have done now about half a year. After much trouble with workmen I am now almost settled; my family being, myself, my wife, Jane, Will. Hewer, and Wayneman, my girle’s brother.

Myself in constant good health, and in a most handsome and thriving condition. Blessed be Almighty God for it. I am now taking of my sister to come and live with me. As to things of State.—The King settled, and loved of all. The Duke of York matched to my Lord Chancellor’s daughter, which do not please many. The Queen upon her return to France with the Princess Henrietta. The Princess of Orange lately dead, and we into new mourning for her.

We have been lately frighted with a great plot, and many taken up on it, and the fright not quite over. The Parliament, which had done all this great good to the King, beginning to grow factious, the King did dissolve it December 29th last, and another likely to be chosen speedily.

I take myself now to be worth 300l. clear in money, and all my goods and all manner of debts paid, which are none at all.

It’s the bit about the plot that makes January an absolutely fascinating month.

For Pepys, it kicks off on the morning of the seventh, when:

news was brought to me to my bedside, that there had been a great stir in the City this night by the Fanatiques, who had been up and killed six or seven men, but all are fled. My Lord Mayor and the whole City had been in arms, above 40,000.

It’s quite a disturbing story, though it doesn’t stop Pepys from going to the theatre and a dinner party that evening. The Fanatiques, it will turn out, are Fifth Monarchy men. Led by Thomas Venner, they believe it’s their mission to bring King Jesus to the throne, so that he can establish the Millennium and rule England with a puritan fist.

A day later, Pepys reports that the Lord Mayor has pulled down a Fanatique meeting house.

On the ninth, he reports on the swirling rumours and chaos:

Waked in the morning about six o’clock, by people running up and down in Mr. Davis’s house, talking that the Fanatiques were up in arms in the City. And so I rose and went forth; where in the street I found every body in arms at the doors. So I returned (though with no good courage at all, but that I might not seem to be afeared), and got my sword and pistol, which, however, I had no powder to charge; and went to the door, where I found Sir R. Ford, and with him I walked up and down as far as the Exchange, and there I left him. In our way, the streets full of Train-band1, and great stories, what mischief these rogues have done; and I think near a dozen have been killed this morning on both sides. Seeing the city in this condition, the shops shut, and all things in trouble, I went home and sat, it being office day, till noon.

Notice it’s just hysteria, no one actually sees any Fanatiques. In fact, the next day he learns from a clerk that there were only ever about 30 Fanatiques on the loose, though in broad daylight they managed to put the “King’s life-guards to the run, killed about twenty men, (and) broke through the City gates twice”.

So people are on edge. It’s made worse when the Queen’s boat runs aground, forced to turn back to England when Princess Henrietta becomes the third member of the Royal Family to fall ill to measles. It feels like a bad omen. And there are guards everywhere. In fact, it’s decided that the navy men should all go out of town to check on things, and Pepys is to go with Colonel Slingsby to Deptford and Woolwich. But before he can leave, his buddy Captain Morrice wants Pepys to borrow a horse so they can ride around all night looking for rogues alongside the Lord Mayor and the City Guards, though Pepys begs off.

At Deptford, Pepys realizes being a senior clerk in the navy has its perks, because all the officers are coming to him cap in hand, and he’s treated “with so much respect and honour that I was at a loss how to behave myself.” But the next night brings danger. An alarm sounds and the seamen are mustered and quickly armed with fierce handspikes. There must have been a lot of nervous waiting around, people’s nerve getting the better of them as they tried to figure out the cause for the alarm. Eventually they learn that five or six men rode through the town and shot at the guard. The next day arms arrive from London and Pepys distributes them accordingly.

The rest of his tour goes smoothly, and on the 19th Pepys is back in London, and he happens to see Thomas Venner being pulled on a sledge, off to be hanged, drawn and quartered along with other Fifth Monarchist men.

Pepys’ business for the rest of the month is about working with a Parliamentary Commission to determine if and how they’ll pay off the navy (ie paying the crews of all the ships). In this work he learns he’s now of an equal station as his old school master. He seems pleased to be entrusted with large amounts of money, and spends time at the book market in St Paul’s Churchyard. A captain sends him a pair of canaries.

On the 28th, he learns that Oliver Cromwell’s body has been dug up and is to be hanged and beheaded as a sort of rejoinder to the Fifth Monarchists and anyone else who might oppose Charles II. A woman accidentally spits on Pepys at the theatre, “but after seeing her to be a very pretty lady, I was not troubled at it at all.”

The 30th is a day of fasting, as Cromwell’s body is to be hanged. Pepys’ wife goes to see the hanging, as does Pepys’ fellow diarist Thomas Rugge, who offers this record of the event:

Jan. 30th was kept as a very solemn day of fasting and prayer. This morning the carcases of Cromwell, Ireton, and Bradshaw (which the day before had been brought from the Red Lion Inn, Holborn), were drawn upon a sledge to Tyburn, and then taken out of their coffins, and in their shrouds hanged by the neck, until the going down of the sun. They were then cut down, their heads taken off, and their bodies buried in a grave made under the gallows. The coffin in which was the body of Cromwell was a very rich thing, very full of gilded hinges and nails.

Pepys, however, uses the day to go for a walk with Sir W. Pen in the Moorefields ‘to have a brave talk,’ and here they spy some of the navy’s younger clerks skipping work to enjoy themselves outdoors on what happens to be a very pleasant day. In fact, Pepys notes it’s been a strangely warm month, with “no cold at all; but the ways are dusty, and the flyes fly up and down, and the rose-bushes are full of leaves, such a time of the year as was never known in this world before here.”

So that’s January 1661 for Samuel Pepys. An uproar in the city, but he continues to rise in status and wealth.

Cromwell’s head, by the way, was put on a spike and displayed at Westminster Hall until at least 1684, at which time it quite literally fell into private hands and became something of a curiosity.

Most interesting acquaintance: Pepys shared the boat ride to Deptford with Major Waters, a friend of Colonel Slingsby, “a deaf and most amorous melancholy gentleman, who is under a despayr in love, as the Colonel told me, which makes him bad company, though a most good-natured man”.

Plays of the month: On the third Pepys sees Beggar’s Bush, a comedy, which he says is very well done, and the first play he’s ever seen with women actors. On the seventh, he sees Ben Johnson’s The Silent Woman, again, in which Edward Kinaston plays three roles: a poor woman in ordinary clothes, a gallant woman in fine clothes (and “clearly the prettiest woman in the whole house”), and, finally, a man. On the eighth Pepys sees The Widdow, “an indifferent good play,” ruined because the women don’t seem to know their lines.

Links

The brilliant Renaissance artist who ‘lived in filth and ate only eggs’

#Heistwatch: How London hotel sting caught Swiss museum heist thieves

Diary of the Wolf (again)

And congrats to mufo Geoffrey Morrison on being longlisted for the Dublin Prize! You really should check out his novel, Falling Hour

Bluesky invitation: bsky-social-brmrd-qut54

Thanks for reading, especially if you’ve made it this far. And special thanks to OMQ editors Julian Barona, Graham Thomas Wilcox, and Caitlyn Emily Wilcox. This has been Adam’s Notes for January 22, 2024. My name is Adam McPhee, and you can find me on Twitter, Bluesky, Letterboxd, and Goodreads.

The Trainebands were local defence militas, sort of an armed neighbourhood watch.