Friday May 29, 1663 was a holiday, King Charles II’s birthday—though in his diary, Samuel Pepys accidentally put it down as the anniversary of Charles’s coronation. Still, Pepys took the day off, wandering the city with his buddy and sometimes rival, Mr. Creed. They were annoyed that the churches were all empty except for poor people, so they went to a coffee house, then to see a play, then to an alehouse, “and there having drunk,” they hit upon another idea: they went to the Gatehouse at Westminster to look at the German princess. Pepys doesn’t record his reaction to seeing the princess, just that afterwards he left Creed to go see his brother. Maybe it was a disappointment. It was a curious place to find a princess, though, because the Gatehouse was a prison mostly used for debtors (Pepys himself would have a brief stay there in 1690 when he was suspected of Jacobitism).

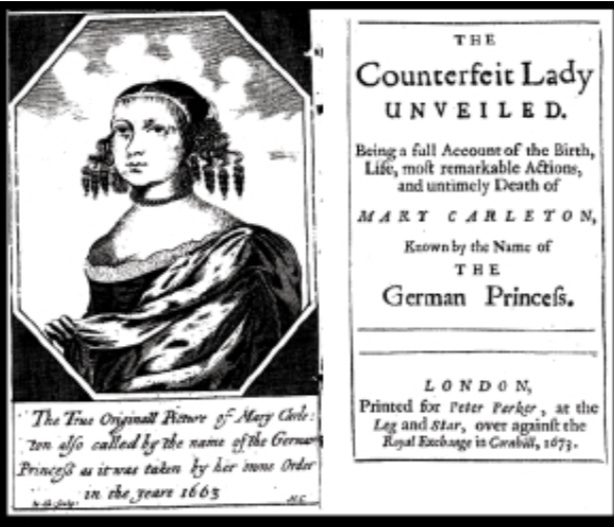

The thing is, Princess Henrietta van Wolway of Cologne wasn’t really a princess. She just called herself that. Depending on who you asked, her real name was Mary Carleton. Or Mary Stodders. Or sometimes Mary Moders. At times she was also known as Maria Darnton, Mary Blacke, Mary Kirton, Maria Lyon and Mary Carlston. She was the original hipster grifter. She liked to tell people that she was the daughter of one Henry van Wolway, Lord of Holmstein, and that she’d come to England to avoid an unwanted marriage to an eighty-year-old German count who conducted himself like a lowly soldier.

Earlier in the year she’d married the law student John Carleton. His parents were disappointed to find out she wasn’t rich (she went around with fake jewels and arranged for fake letters to be sent to her confirming her story), and became incensed when they received an anonymous letter claiming she’d been married twice before, first to a shoemaker, then to either a bricklayer or a surgeon in Dover. In both cases she was alleged to have stolen their goods and run off. She wasn’t a princess. She was a bigamist.

While waiting for her trial, she and John both put out pamphlets attacking each other. Other pamphlets appeared as well. One anonymous pamphlet attacking Mary was titled “The Lawyer’s Clerk Trapanned by the Crafty Whore of Canterbury.” It changes her assumed aristocratic title Henrietta Von Wolway to the pornographic Henrietta Maria da Vulva (at the time ‘trapan/trepan’ seems to have been slang using trepanation in the sense of drilling a hole in the skull to refer to a prostitute who ripped off her clients and thus making them look stupid/brainless).

“The Great Trial and Arraignment of the German Princess” was a pamphlet recounting the trial. It has her “at the bar… playing with her fan before her face, beholding the bench with a magnanimous and undaunted spirit.” In her defence to the accusation that nine years ago she married a shoemaker and had two children by him, she insists that today she is only twenty-one years old, and thus the accusation is impossible. The bricklayer testified that she was his wife, but Mary points out that he had to put his eyeglasses on to look at her before he swore to it, causing the jury to doubt his claim. An important witness—one of her previous husbands—couldn’t afford to travel to London to testify. She said those against her were bribed or otherwise coerced, and it helped her case that she remained confident while they were intimidated by the justice system. The judge asked where she was born, and in broken English she said near Cologne. She said she married John Carleton not to trick him, but because she was tricked by him, or rather by his parents, who made it sound like they were lords, and arranged the match hoping to get their hands on Mary’s wealth. Both side, it seems, were trying to scam the other. But Mary pointed out she only claimed to be a princess, not rich. She joked that in the end the Carletons only cheated themselves.

The pamphlet, of course, was one-sided, and omits the evidence given against her. But Mary was acquitted and it was generally agreed that she turned her testimony into a great performance. The question of her social status was ultimately irrelevant to the trial, and while she insisted she was an aristocrat, she had a knack for avoiding the details when it was impolitic. Meanwhile the Carleton clan's case relied too much on hearsay, which was inadmissible.

The trial was the talk of London. On June 7, 1663 Sir W. Batten’s wife interrupted a business meeting between Batten and Pepys, and “inveighed mightily against the German Princess.” Pepys, not really a fan of Lady Batten, was “high in the defence of [Mary's] wit and spirit, and glad that she is cleared at the sessions.”

Still, winning the trial meant that Mary was legally married to John, meaning the Carleton’s controlled all of her assets (including the jewels which may have just been overvalued as opposed to outright fakes), and they weren’t letting her have it.

The trial gave Mary a taste of fame and evidently she liked it. In 1664 she had her pamphlets (she wrote, or more likely had someone else ghostwrite, two more after the trial) turned into a play, written by one John Holden. Holden wasn’t much of a playwright, evidently: as far as I can tell, he’s only credited with one other play, “The Ghosts,” which Pepys dismissed as “very simple” when he saw it in 1665. Mary insisted on playing herself in Holden’s “The German Princess.” Pepys didn’t care for it: “never was any thing so well done in earnest, worse performed in jest upon the stage; and indeed the whole play, abating the drollery of him that acts her husband, is very simple, unless here and there a witty sprinkle or two.”

Her acting career a bust, Mary was back to square one. She fell off the radar for a time (her wikipedia entry says she fell back on her old tricks, duping relatively well-off men into thinking she was a fallen aristocrat, and well I don’t doubt that she was up to no good, I believe the source here is one of the later, less reliable pamphlets).

Who was the real Mary? Her accusers have her as the daughter of a fiddler from Canterbury, part of the immigrant Dutch community. She had an aptitude for languages and her father’s work might have given her some access to the rich. One source calls her “Dutch-built … a stout Fregat.” Pamphlets have her speaking in broken English, but often hinting that this was for show, like when she says she doesn’t ‘kun-now’ her accusers. Another says she was a child prodigy, and did accompany some lady of standing on a trip to France, where she picked up the aristocratic manners that she insisted on following in later years. It was generally agreed that she was very intelligent, very confident, and had (or at least confidently affected) aristocratic manners, but often faced setbacks due to her habit of petty theft. One of her pamphlets was addressed to Prince Rupert in the hope that he might take an interest in her—no luck there.

Mary returned to the public’s attention in 1671, arrested for stealing a silver tankard. Her punishment was that she was to be shipped to the penal colonies in Jamaica. It was a harsh sentence. She would probably be forced into prostitution and/or indentured servitude, and certainly she’d be looking at an early grave.

And yet England didn’t forget her.

A new pamphlet began to circulate, claiming to have been written by Mary “to her fellow sufferers in Newgate (prison); wherein she, or the author that writ it, gives a drolling, romantic account of her voyage thither, arrival there, and several other fabulous fancies.”

Mary—or whoever authored the letter—wrote:

I came to the desired haven with a prosperous gale. Where I no sooner arrived, but I was, contrary to expectation, treated en Princesse, and accommodated like my self. But one thing I have omitted; when I first set sail from England I was…despised as the base brat of a country fiddler…I fled to my old Asylum, the never failing refuge of a charming tongue and ready wit, and so had both my lodging better’d and my commons amended…At my landing, instead of a barborous slavery…I was immediately environed with a crowd of admirers. And no sooner was my name heard, but it echo’d into the remotest parts of the island and drew a wonderful confluence of the more vile and dissolute people to my habitation.

The letter was almost certainly a hoax, but Mary did not meet her end in Jamaica.

In 1672 a turnkey at Newgate recognized her among the prisoners in his charge. Somehow she’d made it back to London from Jamaica—which was, of course, illegal. Instead of this new theft she was in prison for, she was now sentenced to death. She claimed that she was pregnant and thus deserved leniency, but examiners found that wasn’t the case.

On January 22, 1673, she was hanged at Tyburn.

More pamphlets followed in the years after her death, turning her into a sort of folk hero. In one, she seduces the son of a rich man, gets him dead drunk, then takes his money and sells him into slavery on a ship bound for Barbados. Another has her earning her freedom in Jamaica after foiling a plot to murder the captain of the ship taking her there, and then charming the governor. In one, she and some friends throw a birthday party and invite her landlady, and when the landlady falls asleep, they rob her.

In 1673, Francis Kirkman wrote The Counterfeit Lady Unveiled, supposedly a biography of Mary. He claimed to have inside sources, even saying he spoke with Mary and her husband John and a number of witnesses, and that he himself had relatives defrauded by her, but really Kirkman’s was just recounting stuff from the pamphlets and the stories Mary was known to have told, adding little touches of verisimilitude, fictional emotional reactions, and smoothing away discrepancies as he saw fit. He even gives her some character development, allowing her to change over time. Ernest Bernbaum argued the book was an important (albeit overlooked) step away from the romance narrative and towards the novel.

Later still, Mary’s story was—along with the case of the pickpocket Moll King—became one of the inspirations for Defoe’s Moll Flanders.

Sources

The Mary Carleton Narratives, 1663-1673: A Missing Chapter in the History of the English Novel by Ernest Bernbaum

Counterfeit Ladies by Janet Todd and Elizabeth Spearing

Mary Carleton’s false additions: the case of the ‘German Princess’ by Kate Lilley

The Diary of Samuel Pepys

More Pepys posts

January 1662: No more drinking, no more theatre

February 1662: Dancing mania, Valentine’s, arquebus headshot

March 1662: A leather submarine?

April 1662: Sneaking around on his wife

May 1662: Lustful nuns and a grim reminder

June 1662: Pirates, a scam, maggots, and voyeurism

July 1662: Why can’t the King command the rain?

Instagram | Goodreads | Letterboxd | Bluesky

Hello there Adam, I see your posts often in my feed, and I must say I do enjoy what you share.

I thought I’d introduce myself with one of my latest works, you may enjoy it:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/tartaria-in-the-18th-century?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios