Double-Edged Waste Flowers: an interview with Bryn Hammond

Adam's Notes for October 15, 2024

Reminder: My short story “The Debtor’s Crypt” is out now in Hellarkey III.

This week I’m interviewing author Bryn Hammond. I believe I met Bryn a few years ago through twitter, back when I would get bored and search random keywords related to the Orlando Furioso. It quickly became apparent that not only had she read it well enough to know it on a deep level, but she’s also familiar with a lot of the scholarship surrounding it. Her real passion, though, is the Mongolia of Ghengis Khan—or Tchingis Khan, to use her preferred transliteration.

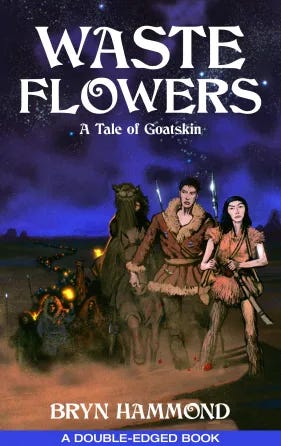

Her latest, Waste Flowers, is a reflection of this. It’s one of two Mongolia-themed novellas collected in a single book in the style of the old Ace Doubles, out soon from Brackenbury Books. The Double-Edged Sword & Sorcery Backerkit campaign to fundraise for the book’s publication succeeded just as I started writing this intro, but there’s still a few days left and a few stretch goals they’re hoping to reach. Be sure to check it out!

Adam: Can you tell us a little about New Edge and the unique format of your novella?

Bryn Hammond: New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine has sprouted a book arm, Brackenbury Books, and this Double Edge is its first adventure. It’s my novella and another by Dariel Quiogue, back to back. Flip the book around and upside-down when you’re done with one, you have the other. That means two great pieces of cover art, by Goran Gligović for mine and Artyom Trakhanov for Dariel’s Walls of Shira Yulun. Internal artists are Crom and Gary McCluskey. If our Backerkit campaign reaches a stretch goal – and there’s still time! – we’ll also get a two-page colour illustration of our heroes face to face by Sajan Rai.

You’ve spoken strongly against the common caricature of Ghengis Khan’s Mongolia as a place where vast hordes ride around in barbarian splendour, motivated only by stomping their enemies. For example, your article for the Asian Review of Books really opened my eyes about how much more there is to this historical period. For readers new to your writing, could you maybe elaborate some of the differences between the popular view of Ghengis versus the Tchingis Khan who looms over Waste Flowers?

In Waste Flowers, we first hear of him through the half-ignorant gossip of my bandits in Tangut. These are ex-villagers who know nothing about nomad life but are anti-authoritarian and enjoy talking up his bloody elimination of petty lineages up in the barbarian north. They tell us Tangut’s aristocracy is afraid his example might fuel class discontent in Tangut. In steppe society Tchingis has positioned himself as anti-prince, anti-nobility, since the princes and nobility of the steppe have been sponsored by Chinese states – funded and corrupted.

On one level, this is a case of the valency Tchingis Khan had and has for different audiences. Whether to scaremonger or to co-opt, he’s been used then and ever since. But it points to a revolutionary Tchingis Khan, whom I do portray as so radical a social innovator as to invoke the word revolution. In Waste Flowers he’s on the cusp of his off-steppe wars, he’s at the height of having united the peoples of the steppe, a steppe that has been kept fragmented and weak for centuries by Chinese states. A couple of characters call him a visionary.

As for any major figure of the 12th-13th century, especially such a controversial one, there are conflicting takes. I write the Tchingis Khan I am interested in writing. I don’t insist he’s the true one, but I promise you he is possible, from every piece of evidence we have. Early on I was influenced by a certain view of his life as a tragic trajectory. Periods of unification of a people, in a movement that also involves a fightback against encroachment, against the interference of a gigantic neighbour, always have an idealism, a high-mindedness. And when you strengthen and equip your society for that fight by introducing a greater egalitarianism in both class and gender, that’s going to be intoxicating, to them and to us too. After this comes a collision with the outside world, the settled world that has its age-old prejudices against nomads, and whose demographics confuse a Mongol straight off the steppe. They have crowd-shock, they have city-shock. A lot of the cataclysm in that encounter happened by accident.

I am a tragedy addict, and a few of my most influential novels (all right, it’s Dostoyevsky) are about people who are well-motivated but go too far in a good cause, or who are led astray by an internal logic, to become less than themselves, a worse self. So that’s the trajectory I had in mind for him. In my Amgalant I didn’t stint on the first element, I set him up as nearly a saint, ahead of a plunge into the evils of those wars. In Waste Flowers, dark things are on the horizon, adumbrations of one of the worst wars in history. The state of Tangut itself is going to be wiped off the map, in a destruction prefigured in my early scene where bandits gloat at the fear of their upper classes.

Mind you, I am never going to replicate a model whereby civilization is an innocent victim of barbarism, and had everything valuable in it. The evidence on Tangut upturns a steep inequality and a worsening crisis of class exploitation on the eve of the Mongol wars. My bandits’ lives, and other underprivileged you meet in the Goatskin tales, look at that.

Something that really stuck out to me about Waste Flowers is the worldbuilding. I think one of the reasons medieval Europe is often the go-to setting for this kind of thing is that it’s more familiar, there are more sources available to English language readers and writers, whereas there’s a fear that anything touching on Asian history is going to be hard to follow, yet you have a real mastery for laying out stuff like factions and places names and that sort of thing, all without boring us with exposition. And I feel like I could pretty confidently guess where you’re breaking off from more established history to your own informed speculation. How did you manage to accomplish that?

I’d say my main strategy here is to have my people invested, intellectually and emotionally, in the stuff I need to convey, that is, the issues of their day. To make it a personal story and character-centric, where folk have exchanges of views in their habits of speech, about what affects them. So, yes, I do most of this through speech. It’s not going to sound like exposition when people are having a real conversation about matters they have a vital part in, that they care about as urgently as we care about big questions in our present. I think, just to keep in mind that they are living through the thing, enables you to give sufficient information to the reader in an immediate way.

I think readers are really going to love Goatskin. Can you tell us a little bit about who she is and maybe how she came to you and what she’s doing with the Wild Geese when we first meet her?

I hope so. To focus on her motivations: the first sentence concerns the fences she feels around her, and she is haunted by walls throughout, figuratively and otherwise. That’s because she’s a nomad in a settled society, her tribal people living in an enclave within Tangut State. In this story she escapes to the high steppe of independent nomads, now run by a man who presents himself as a champion of nomads right along the fringes between the steppe and sown. That excites her, and she convinces her girlfriend to go too, who leads the Wild Geese bandits. Goatskin’s a bit anxious because her girlfriend, like most bandits, is very ex-village, and she fears she’s still got a little of a villager’s dim view of nomads.

As Goatskin experiences the open steppe, she reveals an aspect of almost spiritual search, away from the official state religion that has been imposed on her people. But her footloose attitude whereby she can’t join ranks, whether that’s the community of bandits her girlfriend is committed to, or whether that’s an army even in the service of a cause she might believe in, continues to cause her conflict.

You’ve written about this period before in your novel Amgalant, but that was more straightforwardly historical fiction, whereas Waste Flowers is historical fiction blended with the fantasy of sword and sorcery, right? How did you balance the competing expectations of the genres this time around?

I enjoy the metaphors of fantasy which I can’t use in historical. Do I want to spotlight the ancient aristocratic hunt where ‘wastage was prestige’? (see Thomas Allsen’s The Royal Hunt in Eurasian History for staggering statistics). On the second page of Waste Flowers, actual ghost chariots can drive into sight and hunt down my humans in the old style. It’s still historical, it’s commentary informed by a history book, it’s true, it’s just a different mode. It’s in metaphor, right?

That’s how I go on, turning historical curiosities into active monsters, walking into the world of the dead as Mongols, or one Mongol in particular, conceived it. Honestly you can just as well call it historical fiction, written in an imagery not limited to realism.

I love historical fiction in whatever mode, in fact I love the experimental end where figments of people’s imagination might walk and angels intervene. It’s more a spectrum than an either/or. I prefer historical readers to be a bit flexible, there’s a hundred ways to write it. And still converse with the meanings of history.

I found the novel’s action worked really well. I feel like that sort of thing too often gets bogged down in choreography, but here I feel it’s more about tactics, characters working through the real or fantastic logic of the battles they’re in? Does that make sense? What’s your approach to writing action?

I like how you describe it. I definitely want a human inflection on the action, and avoid blow-by-blow choreography, as there’s nothing I find more skippable when reading.

In Amgalant I was challenged by the number of battles I had to write, and I made myself a rule that I had to approach each one in a new way, with a new style or a new slant or a new mood. It had to be situational. What did that particular battle mean, or feel like, for the people involved, for my point of view characters, and how does that give me a facet I haven’t done before?

Tactics, the thinking behind a battle – Mongols being such intriguing, clever tacticians – and the stakes or the conditions as a self-propellant logic, these are a couple of ways in, and through. I dabble with stylised action too, though less in Waste Flowers, and that’s … because I like it. In short, action is one area where you’ve got to shake it up, if you want your reader to be seat-of-the-pants and not glazed over. Contingency is a key word of mine, to get away from too much forethought or author’s hindsight, less like a military textbook. Chase the experience.

Of this new crop of writers trying to reinvigorate sword and sorcery as a subgenre of fantasy—I’m thinking of people like yourself, Jon Olfert, Matt Holder, Graham Thomas Wilcox, and publications like New Edge and Old Moon Quarterly—there seems to be more of an engagement with history and history writing than in the past, when it was all pastiches of Conan. It feels like there’s more of an attempt to work out past logics and mindsets, and to recover some of the pleasures of that kind of writing that wouldn’t necessarily be conveyed in today’s history books. Do you think there’s something to that?

I love this observation. It’s true, though I hadn’t pinned it down like that. I think New Edge Sword & Sorcery’s quest for more diverse settings, as well as its avoidance of Orientalising or exoticising them, has led inevitably to a groundedness in distinct histories. While OMQ, from their editorials, prize medieval primary sources as direct inspiration for fantasy. Go direct to source, you know?

I am a big believer in that. I grew up on ancient and medieval fictions, epic and romance, as my road into history, into understanding how folk in other times and places thought and felt. I still tend to preach that a great way into the past is to read its imaginative works – not just its real-life records. You’ll encounter more than from a secondary source, a history book. That’s why my Amgalant went in through the Secret History of the Mongols. You and I, if I remember, came to each other’s notice from our shared enthusiasm for the Italian Orlando romances. Graham Wilcox writes editorials on medieval romances, I love that for sword & sorcery or for weird fiction, because of course these were the S&S and Weird of their day. But if you don’t go direct to source, if you derive your fantasy ideas from other contemporary fantasy fiction, those ideas dilute, fantasy goes more thinly medievalesque without a real attachment to the medieval.

To me, the purpose of historical input is to get our heads out of the loop of the contemporary – to meet the truly strange. Even one’s imagination is stuck in a loop if not exposed to the raw past with its alien ways of thinking and feeling. I am keen on emotions history, the study of emotions in the past. That’s kind of at odds with a truism often used to sell historical fiction, that across settings human emotions remain a universal, are recognisable or the same. I want to read about emotions and mindsets that aren’t the same as ours.

And I think sword & sorcery, with its in-built distrust of modernity, is a hospitable vehicle for this practice, which is one step towards a stranger fantastic. Yes, I can see this as a strength in current S&S. I like when Jon Olfert writes about cultural intersections in prehistory, animals as different Peoples with different crafts, or tries to get into the mind of a mammoth. Graham Wilcox is clearly interested in a resurrection of language from medieval sources – and language builds the brain, as Stuart Clark’s Thinking with Demons taught me. Matt Holder you highlighted in a previous interview, his interaction with Milton and portrayal of religious thinking.

Something that differentiates this from the old Ace Doubles (as far as I know) is that there’s a uniting theme, in that both you and Dariel Quiogue have written novellas of Mongolia. Did you two coordinate at all, trying to tie your visions of Mongolia together, or were you both just doing your own thing?

We did our own thing. We didn’t coordinate except to communicate our basic plot so that we don’t tread on each other’s toes or both feature the same device. Dariel, Oliver and I talked, though, through the process, and consulted each other when we had craft or research questions.

Since we went our own way, in our own voices, I delight in the synergies that our tales ended up with. Dariel and I both wish to centre the Mongols, to see from a Mongol perspective, and our novellas are both set on the frontiers in between China and the Great Mongol Ulus or its fantasy stand-in. This has led to a nice amount of agreement, of harmony in our accounts.

Can you recommend some other books, fiction or nonfiction, on Tchingis Khan’s Mongolia?

As you suggested in your first question, I am strongly driven to undo negative stereotypes of the Mongols. My fiction struck out in a direction unseen in what was available in English, original language or translated.

I’ll stick to three nonfiction books. The first two I also reviewed for the Asian Review of Books, where my goal was to bring in front of a general audience works of scholarship that they might turn to instead of a dodgy podcast or inexpert popular history.

Sudden Appearances: The Mongol Turn in Commerce, Belief, and Art by Roxann Prazniak, reviewed here, is a fascinating exercise in cultural history: material, intellectual, art history. It explores the connected Mongol world of the thirteenth century through case studies of innovations that popped up because of an unprecedented transmission and interplay between cultures.

Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire by Anne F. Broadbridge, reviewed here, isn’t only a look at women, because Broadbridge’s attention to them changes how we understand the operation of Mongol politics.

It’s so important that we see steppe politics as a complex subject, not a crude and simple slug-fest for power. I recommend Michael Hope’s Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran. To quote: ‘The Secret History is the only history committed to the collegial side of Mongol political ideas, split post-Chinggis into collegial and patrimonial, both of which claimed true descent from Chinggis and the jasaq [his law code]. Most histories being told by patrimonial interests, the collegial presence has been obscured.’

You can bet I’m on the collegial side of that ideological struggle. No wonder I have so much time for the Secret History of the Mongols. Its having lost out reminds us of something vital in my eyes, how enormously the Mongol condition changed within a lifetime. I wrote a blog post ‘On Change’ to alert us to assumptions we shouldn’t make, things we shouldn’t backdate. In Waste Flowers, where we see Tchingis Khan as a revolutionary event, this appreciation of change still applies.

Thanks Bryn!

Bryn is one of those writers who excels at both fiction and criticism, so I’m glad I had the chance to pick her brain about Waste Flowers. She’s done a number of other interviews for this project as well. In particular, I recommend checking out this one over on Eric de Roulet’s blog. And you can find more linked on the Backerkit campaign page. Be sure to check it out.

I haven’t yet read Dariel R.A. Quiogue's Walls of Shiraa Yulun, the other novella in this project, but I am looking forward to it and I’ve enjoyed his short fiction in a few different venues now, including his “The Marchers in the Fog,” which was published alongside my Pepys-werewolf story in Old Moon Quarterly #6.

Bryn Hammond lives in a coastal town in Australia, where she likes to write while walking in the sea. Bryn’s first love was epic – Beowulf, the Iliad – and steppe epic has been her main enthusiasm for twenty years. Her Amgalant novels tell the less-heard story of Temujin before he became the great conqueror Chinggis/Genghis Khan, his beginnings as an outcast, his struggle to unite the peoples of the steppe. Her scholarly work includes Voices from the Twelfth-Century Steppe, on how to listen to the Secret History of the Mongols. Her Goatskin tales can be found in the pages of New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine. You can visit her blog here and find her self-published work here.

Adam McPhee is a Canadian writer who lives in Alberta. His fiction has appeared in venues such as Wyngraf, Old Moon Quarterly, Great Ape Journal, Ahoy Comics, and has been longlisted for the CBC Short Story Prize. He is a submissions reader for Fusion Fragment and writes this Substack newsletter, Adam's Notes. His latest short story, “The Debtor’s Crypt,” is out now in Hellarkey III.

Instagram | Goodreads | Letterboxd | Bluesky

What a splendid interview, all in conversation with what else is going on in the S&S scene. And thanks for the shout-out!