A brilliant comic book and two war stories

Adam's Notes for November 13, 2025

Hello everyone. Hope you’re November’s going well. There should be snow on the ground here by now but there’s none, it’s been bizarrely warm, almost 9C the other day. I’m about to start my annual re-read of the Orlando Furioso, a tradition I picked up from Italo Calvino. Because I’m short on time I’m going to read the Richard Hodgens translation from Ballantine, but because it only covers the first four cantos or something, I’ll switch to the Guido Waldman prose translation for the rest—normally the two volume Barbara Reynolds is my favourite.

Anyway, I’ve got three great books for you this week, a brilliant graphic novel, the non-fiction book everyone’s been talking about, and a forgotten quasi-Canadian war story.

Hobtown Mystery Stories: The Case of the Missing Men by Kris Bertin and Alexander Forbes

Conundrum Press, 2017; 301 pages.

Oh man, this was amazing. I enjoyed Bertin’s short story collection Bad Things Happen, but I put off reading the graphic novel series he’s done with his childhood friend Alexander Forbes because I thought it would be either A) an exercise in nostalgia or B) a series for kids. It’s neither of those things, it’s its own brilliant little world and I can’t recommend it highly enough.

So the kids at Hobtown High in Hobtown, Nova Scotia, have a little detective club that goes around solving mysteries, but now they’re onto something big, and the corrupt adults take their club just seriously enough that they’re constantly trying to sideline it.

It’s full of perfect Maritime details: the way dumb civic boosterism localizes in our area, the faces of old folks who’ve survived a specific kind of poverty, it never goes full Trailer Park Boys, but it has that kind of straight-to-the-point humour and the little tics of language. And yet at the same time it builds its own world, the kids are from an earlier time (Scooby Doo’s Daphne, Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, the older guy vaguely Steve McQueen). There’s something about the fashion I really liked but can’t quite nail down: the author and artists clearly know who these kids are beyond the words on the page. And they have this great way of conveying action. The other element at play here is the influence of David Lynch: there’s a certain High Weirdness at work against the town’s veil of normalcy—or perhaps in collusion with it.

The story is a little frustrating, especially at first. We’re primed to think of this as a detective mystery, a whodunnit, where clues point to suspects and lead us to a culprit, but the logic is too muddled, at times convoluted (which btw is exactly what would happen if you let kids, even gifted ones, try to solve murders). But there’s something more going on here, which should be evident by the time one of the boys spots a weird little gremlin dude making finger guns at the don’t-call-it-a-shriner’s parade.

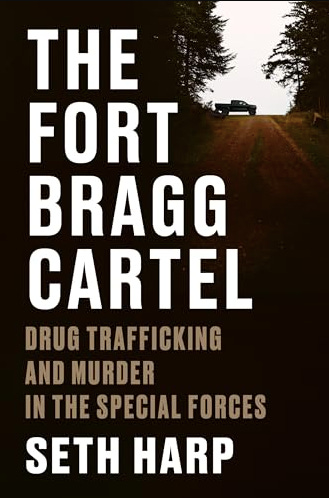

The Fort Bragg Cartel: Drug Trafficking and Murder in the Special Forces by Seth Harp

Viking, 2025; 357 pages.

Reading this, I kept thinking about two things: 1. that byyourlogic tweet about how there's a sort of gladio that isn't gladio per se, just dangerous guys who are never called in. 2. A line in Gwynne Dyer, I think from his book War, about how there's only so much war a person can face before they break down from shellshock, PTSD, or whatever your generation calls it, and the amount of war you can face is shrinking as war itself speeds up.

This book feels like a definitive statement on the War of Terror, or at least this phase of it. Reminded me of Generation Kill, but with a more critical lens, and from the other end of a hard twenty years. Very cinematic. Harp could've just listed all of these parallel cases of under-investigated violence or given us a table, but instead it's a staccato beat, hammering in the point of the book: the war has come home.

The German Prisoner by James Hanley

Exile Editions, 2006; 68 pages.

We’re introduced to O’Garra and Elston as their unit marches back to the trenches. O’Garra was the ugliest man on the worst street of Dublin. His false teeth scared the women, and gangs of children chased him about. So he surprised everyone and joined army. They say he has surrender in the blood. Elston is a cowardly Englishman from Manchester. Their unit keeps stopping and starting, until everyone realizes they’re lost—it’s not a problem in the dark but once the sun comes up they’re screwed. Panic threatens to turn to mutiny as they’re shelled just before dawn.

They spend a day hunkered down, waiting. Then it’s an assault over the top.

It was not the sound, the huge concourse of sound that worried O’Garra. For somehow the earth in convulsion seemed a kind of yawning mouth, swallowing noise. No. It was the gun flashes ahead. They seemed to rip the very sky asunder. Great pendulums of flame swinging across the sky. In that moment they appeared to him like the pendulums of his own life. Swinging from splendour to power, from terror to pity, from Life to Death. More than that. There was a continuous flash away on his right. It was more than a flash. It was an eye that ransacked his very soul.

Elston thinks he’s been killed, but he’s only been hit with their commander’s decapitated head, brains splattered on his forehead. They fall asleep in a pit, and when they wake there’s a German soldier standing over them. He’s just a kid, afraid for his life, no gun, speaks just enough English to surrender. He seems happy to do it, too. He wants out of the war—who doesn’t? But they have no sympathy for the kid, can’t move until the fog rolls out, and a sort of madness takes over the two friends. They reminisce about a woman they raped, and keep reminding themselves that the kid is the enemy, he’s the reason they’re in the trenches, unclean, being shot at, shelled, kept away from women, away from the world of peace. They commit a crime of the most despicable sort, and in doing so forget about the fog and their surroundings…

James Hanley self-published five hundred copies of this short novel in 1931. He had some success with his other writings—Faulkner was a fan—but this one fell through the cracks. How could it not? It was republished by Toronto’s Exile Editions more recently on the somewhat dubious grounds of it being Canadian literature: at the age of fifteen, Hanley jumped ship at Saint John, New Brunswick and enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. I suppose the story also features soldiers in the Canadian army, it’s never said outright but it’s probably the easiest explanation for why an Irishman and an Englishman are marching together.

The German Prisoner has all the rawness of Céline’s stories from the trenches, but none of the style. Still, it’s worth reading just as a corrective for all the times you’ve been sold the idea that Vimy Ridge was something noble and heroic.

I thought you meant: "One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This" when you said "the non-fiction book everyone’s been talking about." I have THAT ....