10 Wild Things I Learned About the Bronze Age from The Horse, The Wheel, and Language

Adam's Notes for October 9, 2025

I spent a big chunk of last week reading submissions at Ex-Puritan. My name is on the masthead now and everything. There’s one story in particular I hope makes the cut for the next issue—fingers crossed. I’m still reading submissions for sci-fi zine Fusion Fragment, as well. Both are a lot of fun. I keep thinking about doing a post comparing the two, and keep putting it off because it’s a dumb idea. They’re both their own things, and the range of stories sent to either is pretty wide.

I guess one thing I could note is that people keep trying to trick Fusion Fragment into publishing AI slop, but that isn’t really a problem at Ex-Puritan. Weird. It’s usually pretty easy to pick them out though, the writing is always uniform in an odd way and there are a bunch of trends that are easy to pick up on (like using the name Lena, for some reason).

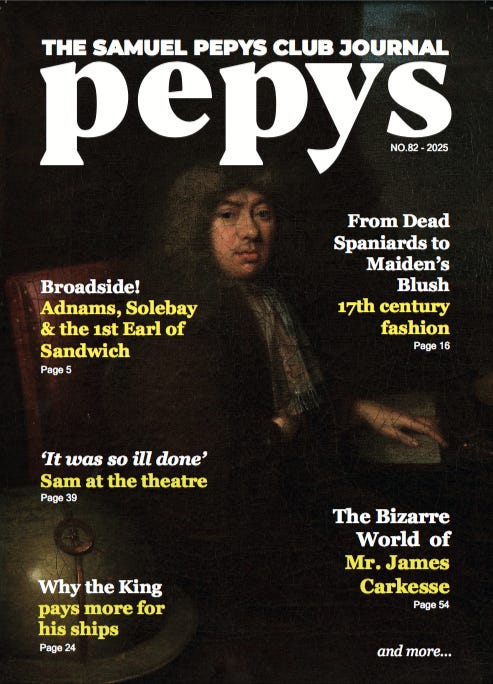

In other news, I’ve had a piece published in The Samuel Pepys Club Journal, looking at some of the plays Pepys saw over the years. I’d share a link to the magazine, but [affecting an aristocratic English accent] it’s club members only, I’m afraid (I myself am not a member, but they were kind enough to send a contributor’s copy). Huge shout out to club secretary Lucie Skeaping, who edited my piece.

Anyway, I realized I write a lot in this newsletter about the novels I read, but not as much about the non-fiction I read, so I thought a sort of list format would be a fun way to change that. Like Pepys, David Anthony’s The Horse, The Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World is a book I’ll always associate with the pandemic. Everyone just seemed to be reading it at some point, discussing it in twitter group chats. It combines archaeology and linguistics to look at prehistoric steppe peoples, and the book is just endlessly fascination.

So, without further ado, here’s twelve things I learned from The Horse, The Wheel, and Language.

The Swaedish list. So this guy Morris Swadesh, a linguist, compiled the core vocabularies of a bunch of languages and looked at their replacement rates of core words over time, discovering that most languages have about a 20% replacement rate per 1000 years. Outliers are Icelandic, which has a very slow replacement rate of only 3% per 1000 years, and English, which has a rapid replacement rate of 26% per 1000 years, and Australian aboriginal languages, which “do not seem to have a core vocabulary—all vocabulary items are equally vulnerable to replacement. We don’t understand why.” A ten percent replacement rate seems to be enough to make languages mutually unintelligible.

Eating fish regularly throws off radiocarbon dating: “Fish absorb old carbon in solution in fresh water, and people who eat a lot of fish will digest that old carbon and use it to build their bones. Radiocarbon dates on their bones will come out too old. Dates measured on charcoal or the bones of horses and sheep are not affected, because wood and grazing animals do not absorb carbon directly from water like fish do, and they do not eat fish. Dates on human bone can come out centuries older than dates measured on animal bone or charcoal taken from the same grave (this is how the problem was recognized) if the human ate a lot of fish. The size of the error depends on how much fish the human ate and how much old carbon was in solution in the groundwater where he or she went fishing. Old carbon content in groundwater seems to vary from region to region, although the amount of regional variation is not at all well understood at this time.”

This one seems kinda dumb once you say it, but I swear it’s cool to think about: Horses were likely first kept for meat, not transportation. Their advantage over other livestock is that they can kick up snow to forage, which cows and sheep are too stupid to figure out. So there’s less need to provide winter fodder. They were first domesticated on the steppe “long after sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle were domesticated in other parts of the world.” They were large and aggressive but could survive winter, so it was worth the effort. As a bonus, they can keep cattle alive, by opening up ground for them in the winter. Even better, “cattle and horse bands both follow the lead of a dominant female. Cowherds already knew they needed only to control the lead cow to control the whole herd, and would easily have transferred that knowledge to controlling lead mares. Males presented a similar management problem in both species, and they had the same iconic status as symbols of virility and strength. When people who depended on equid-hunting began to keep domesticated cattle, someone would soon have noticed these similarities and applied cattle-management techniques to wild horses. And that would quickly have produced the earliest domesticated horses.”

Horse domestication might have come down to humans helping one unlucky stallion get laid... Makes you think... “After the young males are expelled they form loose associations called “bachelor bands,” which lurk at the edges of the home range of an established stallion. Most bachelors are unable to challenge mature stallions or keep mares successfully until they are more than five years old. Within established bands, the mares are arranged in a social hierarchy led by the lead mare, who chooses where the band will go during most of the day and leads it in flight if there is a threat, while the stallion guards the flanks or the rear. Mares are therefore instinctively disposed to accept the dominance of others, whether dominant mares, stallions—or humans. Stallions are headstrong and violent, and are instinctively disposed to challenge authority by biting and kicking. A relatively docile and controllable mare could be found at the bottom of the pecking order in many wild horse bands, but a relatively docile and controllable stallion was an unusual individual—and one that had little hope of reproducing in the wild. Horse domestication might have depended on a lucky coincidence: the appearance of a relatively manageable and docile male in a place where humans could use him as the breeder of a domesticated bloodline. From the horse’s perspective, humans were the only way he could get a girl. From the human perspective, he was the only sire they wanted.”

Another one that sounds kinda obvious when you say it out loud but fun to think about: The wagon opened up the deep steppe because it meant you didn’t have to live within walking distance of a river anymore and you could keep a bigger herd. [Tim and Eric voice] It’s free real estate. “The sight of wagons creaking and swaying across the grasslands amid herds of wooly sheep changed from a weirdly fascinating vision to a normal part of steppe life between about 3300 and 3100 BCE. … As the steppes dried and expanded, people tried to keep their animal herds fed by moving them more frequently. They discovered that with a wagon you could keep moving indefinitely. Wagons and horseback riding made possible a new, more mobile form of pastoralism. With a wagon full of tents and supplies, herders could take their herds out of the river valleys and live for weeks or months out in the open steppes between the major rivers—the great majority of the Eurasian steppes. Land that had been open and wild became pasture that belonged to someone. Soon these more mobile herding clans realized that bigger pastures and a mobile home base permitted them to keep bigger herds. Amid the ensuing disputes over borders, pastures, and seasonal movements, new rules were needed to define what counted as an acceptable move—people began to manage local migratory behavior…. The Yamnaya horizon is the visible archaeological expression of a social adjustment to high mobility—the invention of the political infrastructure to manage larger herds from mobile homes based in the steppes.”

Wagons meant larger herd but also more expensive wives. “The subsequent spread of the Yamnaya horizon across the Pontic-Caspian steppes probably did not happen primarily through warfare, for which there is only minimal evidence. Rather, it spread because those who shared the agreements and institutions that made high mobility possible became potential allies, and those who did not share these institutions were separated as Others. Larger herds also probably brought increased prestige and economic power, because large herd-owners had more animals to loan or offer as sacrifices at public feasts. Larger herds translated into richer bride-prices for the daughters of big herd owners, which would have intensified social competition between them. A similar competitive dynamic was partly responsible for the Nuer expansion in east Africa.”

It was a man’s world but there were tons of women in the kurgan graves. “Among later steppe societies women could occupy social positions normally assigned to men. About 20% of Scythian-Sarmatian “warrior graves” on the lower Don and lower Volga contained females dressed for battle as if they were men, a phenomenon that probably inspired the Greek tales about the Amazons. It is at least interesting that the frequency of adult females in central graves under Yamnaya kurgans in the same region, but two thousand years earlier, was about the same. Perhaps the people of this region customarily assigned some women leadership roles that were traditionally male.”

At one point the author just mentions offhand that the city of Uruk mass-produced ration bowls. Wildly fascinating.

A bunch of supertowns sprung up in what’s now Moldova and Ukraine. They were briefly the largest human settlements in the world, but were also quickly abandoned. Sounds like they weren’t able to organize society at that scale and their defensive advantage was soon lost. “Tripolye towns closer to the steppe border on the South Bug River ballooned to enormous sizes, more than 350 ha, and, between about 3600 and 3400 BCE, briefly became the largest human settlements in the world. The super towns of Tripolye C1 were more than 1 km across but had no palaces, temples, town walls, cemeteries, or irrigation systems. They were not cities, as they lacked the centralized political authority and specialized economy associated with cities, but they were actually bigger than the earliest cities in Uruk Mesopotamia. Most Ukrainian archaeologists agree that warfare and defense probably were the underlying reasons why the Tripolye population aggregated in this way, and so the super towns are seen as a defensive strategy in a situation of confrontation and conflict, either between the Tripolye towns or between those towns and the people of the steppes, or both. But the strategy failed. By 3300 BCE all the big towns were gone, and the entire South Bug valley was abandoned by Tripolye farmers.”

Proto-Indo-European was the hottest franchise on the steppe. “Wealth, military power, and a more productive herding system probably brought prestige and power to the identities associated with Proto–Indo–European dialects after 3300 BCE. The guest–host institution extended the protections of oath–bound obligations to new social groups. An Indo–European–speaking patron could accept and integrate outsiders as clients without shaming them or assigning them permanently to submissive roles, as long as they conducted the sacrifices properly. Praise poetry at public feasts encouraged patrons to be generous, and validated the language of the songs as a vehicle for communicating with the gods who regulated everything. All these factors taken together suggest that the spread of Proto–Indo–European probably was more like a franchising operation than an invasion. Although the initial penetration of a new region (or “market“ in the franchising metaphor) often involved an actual migration from the steppes and military confrontations, once it began to reproduce new patron–client agreements (franchises) its connection to the original steppe immigrants became genetically remote, whereas the myths, rituals, and institutions that maintained the system were reproduced down the generations.”

Reading this really makes me want to revisit The Horse, The Wheel, and Language now. (It's also great source material if one wants to write fiction about ancient people that doesn't follow the most well-worn tracks.)

Oddly enough, I've found a pretty good book-end to Anthony's work is Jack Weatherford's Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. The latter also offers a more nuanced view of steppe society and of cultural and technological diffusion at that time.

I'm not one of the people who were reading The Horse, etc. back when you were, but I'll be reading it now. Just ordered it from the library. If it's as fascinating as you make it sound, I'll buy a copy.